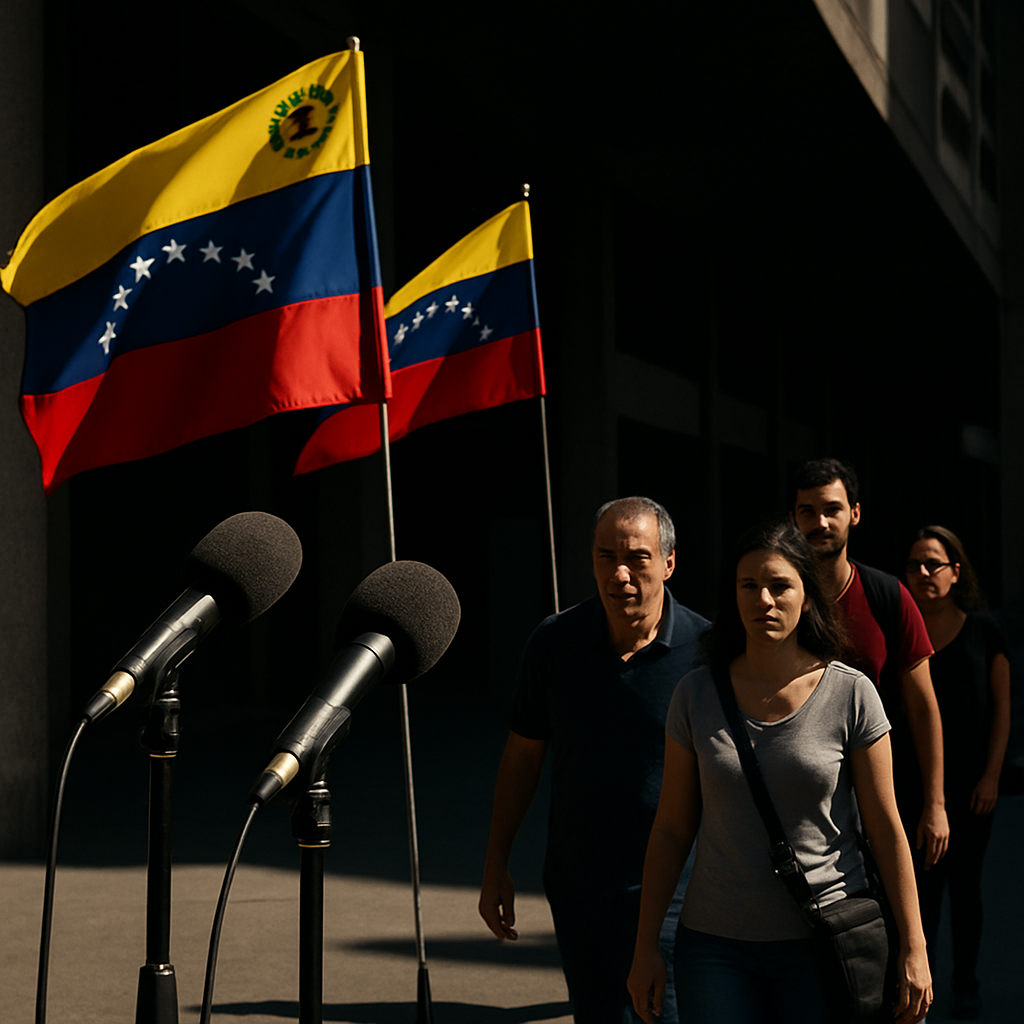

In the wake of the overthrow of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuelan dissidents who spent years in hiding are beginning to reemerge, cautiously testing the boundaries of free expression in a still‑uncertain political landscape. Among them is veteran opposition figure Andrés Velásquez, who recently appeared publicly to demand the release of political prisoners and call for new elections after what he described as the dismantling of Venezuela’s “repressive apparatus.”

The environment remains fragile despite these visible signs of change. Acting President Delcy Rodríguez has promised a general amnesty for political detainees and announced plans to convert the notorious Helicoide prison into a cultural complex. Yet human‑rights observers warn that the country’s basic institutions remain under partisan control and that genuine democratic reform has yet to take root. Pedro Vaca of the Inter‑American Commission on Human Rights characterized the moment as a “temporary loosening” rather than a true opening, saying Venezuela’s civic space “is still a desert.”

Since the disputed 2024 election that ended with Maduro’s ouster under U.S. pressure, Venezuelan media outlets have cautiously reopened their platforms to opposition voices. Venevision and Globovision have both restored limited access to critics once barred from their airwaves. State television, which for years operated as an engine of propaganda, has even begun to air footage showing mild confrontation with political figures — a symbolic break from the total message control of the past decade.

Still, Rodríguez’s allies are divided over how far these changes should go. Hard‑line officials, including Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello, have lashed out at coverage of exiled leaders abroad, warning media outlets not to “play into plots” against the government. Internet restrictions remain in place, and free access to the platform X continues to be blocked following accusations of election interference.

For those like journalist Carlos Julio Rojas, recently freed after nearly two years behind bars, the urge to speak openly outweighs personal risk. Although ordered not to discuss his experience of imprisonment, Rojas ended his silence within weeks, saying that “not speaking was a form of torture.” His defiance underscores both the potential and the precarity of Venezuela’s current moment — a fragile thaw that could either edge the nation toward renewed civic participation or collapse back into repression.

Leave a Comment